The H-1B is an employer-sponsored visa allowing foreign nationals to live in the US for the purpose of working in a specialty occupation. Many international applicants to US MBA programs hope to remain in the US postgraduation for work, and they ultimately need an H-1B to do so.

If you’re an international applying to US MBA programs or currently studying in one, and you aim to work in the US after graduation, this article will tell you what you need to know.

Recent developments have once again put H-1Bs in the spotlight: President Trump just attached a $100k price tag to the H-1B application.

Below, we’ve written about what this change could mean for you.

Foreign nationals who come to the US to earn an MBA (or any other full-time graduate or bachelor’s degree) need to apply for an F-1 visa. This is classified as a “nonimmigrant” visa, meaning it entitles you to stay in the US for the duration of your studies—not to remain permanently.

Following graduation, F-1 visa holders are entitled to stay and work in the US for a period of Optional Practical Training (OPT). This can be an important grace period for those who are seeking, but have not yet secured, H-1B sponsorship.

The OPT period is one year by default, but it’s extended to three years when you major in a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) field. Many MBA programs are wholly classified as STEM degrees; others are not, or only partially—with only certain specializations within the program qualifying as STEM.

All of the top 25 MBA programs in the US are either fully STEM-designated or offer at least one specific track or major that has STEM designation. There are eight programs in the latter group (the other 17 are all fully STEM-designated):

| School | STEM-Designated Pathway(s) |

| UPenn Wharton | Artificial Intelligence for Business; Business Analytics; Business Economics and Public Policy; Business, Energy, Environment and Sustainability; Environmental, Social and Governance Factors for Business; Finance; Operations, Information and Decisions; Quantitative Finance; Social and Governance Factors for Business; Statistics |

| Dartmouth Tuck | Management Science and Quantitative Methods |

| Michigan Ross | Management Science |

| UT Austin McCombs | Financial Mathematics and Management Science; Quantitative Methods |

| Cornell Johnson | Management Science |

| Georgetown McDonough | Management Science |

| Indiana Kelley | Business Analytics; Finance; Marketing; Strategic Analysis of Accounting Information; Supply Chain and Operations |

| UW Foster | Management Science |

International applicants targeting any of these programs will often pursue these STEM-designated pathways (and then a relevant post-MBA role) so that their OPT period lasts three years, giving them a longer window in which to secure H-1B sponsorship.

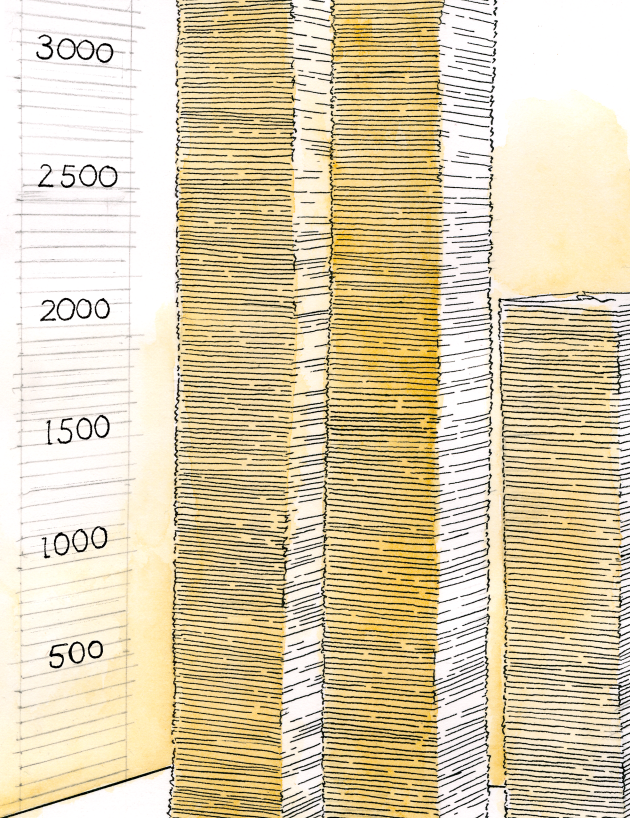

The H-1B visa (unlike the F-1) has an annual cap of 85,000. This is the maximum number of new H-1Bs that will be approved each year. (Some industries are exempt from this cap—educational institutions, among others.)

The number of applications for H-1Bs consistently far exceeds this cap. To decide which applications are selected and subsequently approved, a lottery system is used. This is purely random, meaning that even with employer sponsorship, approval is far from guaranteed.

In 2024, for example:

The good news for MBAs is that 20,000 of these visas are reserved for those with advanced degrees (including MBAs) from US institutions. Those holding such degrees are first entered into the main lottery and then, if they’re not approved, into the smaller lottery for advanced degree holders—effectively giving you two chances at approval.

Like the F-1, the H-1B is a “nonimmigrant” visa. It’s initially valid for three years and extendable for another three. Some H-1B workers, wishing to remain in the US permanently, may begin the process of applying for a green card during this time, again sponsored by their employer, and thus transition from H-1B status to permanent residency.

The term “nonimmigrant” means that both the F-1 and H-1B visas are temporary, and each is valid only for its stated purpose: study or specialized work. So you can’t, for example, remain in the US on an H-1B visa if you lose your job.

“Nonimmigrant” also refers to the perceived intentions of the person requesting the visa. These visas can be denied if you are judged to have “immigrant intent”—that is, if the immigration authorities believe that your real goal is to settle permanently in the US in the future.

We’ve seen a couple of cases where this stipulation has led to complications for MBA applicants.

One applicant, already working in the US on an H-1B visa, had begun the process of applying for a green card. Expecting to have the green card approved in time, she’d begun applying for MBAs.

In the event, her green card process was delayed, and the fact she had begun the process meant she was no longer eligible to apply for the “nonimmigrant” F-1 visa—she’d clearly demonstrated immigrant intent. Ultimately, she had to delay the MBA until the green card was approved.

Separately, an Indian applicant, planning to finance his US MBA through student loans, faced questions about how he would pay off those loans post-MBA if he planned to return to work in India, where salaries are much lower. His visa was denied on those grounds.

It’s important for internationals seeking F-1 or H-1B visas to keep this requirement in mind, understand how it could affect their plans, and tell a clear story about their intentions.

If you have any uncertainty, we always recommend working with an immigration lawyer for clarity on visas and immigration. Many of our clients have had success with Fragomen.

You can, but not on the H-1B visa. This visa is a work authorization entitling you to do specialized work in the US, but not to pursue full-time education.

In order to begin an MBA, you will have to apply for a change of visa status to F-1.

Bear in mind that if you then return to work in the US post-MBA, it will mean reapplying for the H-1B visa and going through the lottery again.

On September 19, 2025, President Donald Trump proclaimed the introduction of a $100k fee to be paid by the firm sponsoring an employee’s H-1B application. This is intended to disincentivize the hiring of foreign nationals for specialized roles in the US.

On October 20, 2025, USCIS clarified that this fee will not apply to those seeking a change of status from F-1 to H-1B status. The fee is instead intended to apply to those making the application from outside the US.

If you’re an international applicant to a US MBA program and you hope to stay and work in the US after graduation, that clarification should be reassuring. Speculatively, this could even improve your chances of securing H-1B sponsorship if it leads companies to favor those already in the US over those currently abroad.

But let’s explore the implications of this news a bit further.

It’s worth emphasizing the duration of this measure. It’s currently effective for one year from the date it was proclaimed—so, until September 2026. It might be extended beyond that, or it might not.

It might not even last that long. At the time of writing, two lawsuits have already been filed: one by a coalition of nonprofits and healthcare firms, challenging the president’s right to unilaterally impose what they characterize as “extortionate” fees; and another by the US Chamber of Commerce, arguing that the presidential proclamation unlawfully overrides the authority of Congress.

We don’t yet know whether such challenges will be successful. But we do know that in the past, Trump has often begun by imposing harsh measures (e.g., tariffs) and then, in response to backlash, reversed course or at least backed down to a more moderate position.

Notably, the proclamation appears to leave the government a high degree of flexibility to waive this fee for certain individuals, companies, or industries. It’s not inconceivable that, for instance, big tech firms could lobby successfully to be exempt.

And, of course, the current administration ends in 2029, after which a new administration may take a very different approach. Those applying for MBA programs that start in 2026 will graduate in 2028; the three-year OPT period discussed above takes them to 2031, well into the next administration, before they need an H-1B.

We don’t know what the program will look like by then, just as we didn’t know five years ago what it would look like today.

Further possible changes to the H-1B program and to OPT have been floated by this administration, but it’s pure speculation at this point what will actually be implemented. Internationals coming to the US these days must, to some extent, be willing to bear with the uncertainty.

Let’s say the fee stays in place. Will firms be willing to pay it?

The answer, if we’re talking about popular target companies for ambitious MBAs, is likely yes.

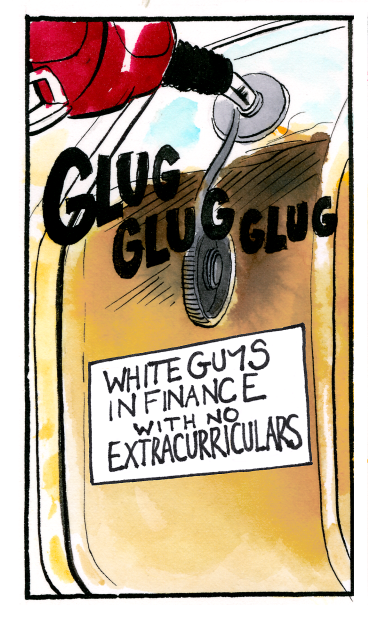

Major beneficiaries of the H-1B program include big tech firms such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, as well as consulting and finance firms like Deloitte and JPMorgan. Such firms are already willing to sponsor employees’ MBAs, to pay huge signing bonuses to candidates, or even to buy them out of their obligations to other firms.

(Say Deloitte paid for your MBA on condition you’d return to work for them afterward. But McKinsey really wants you for a post-MBA role and pays the $150k you owe to Deloitte to “buy you out” for the new role.)

That is, while such firms may shift their hiring priorities to some extent in response to the new fee, they have shown themselves willing and able to absorb similarly large costs for the right candidates. It’s unlikely that a company like Amazon will be easily convinced to stop pursuing H-1Bs.

It’s been argued, therefore, that this policy will have the greatest impact not on the big firms with many foreign employees that make the most use of the program, but on startups and smaller businesses that can’t realistically afford the fees.

Some might claim that business schools will be less receptive to international applicants if they believe they’re now less likely to be hired by US firms. Besides the fact that the fee appears not to apply to changes of status from F-1 to H-1B visas, there’s another objection to this idea:

Universities’ revenues rely to a large extent on international students, who normally pay higher fees. These schools know that administrations come and go, and it’s in their interest to do everything they can, within the bounds of the law, to continue enrolling international students.

Applying for an MBA as a non-US citizen comes with an additional layer of complexity and administration—around visas, but also the application itself.

Many international MBA applicants have difficulty juggling visa requirements and the application process—both of which require the ability to clearly articulate your post-MBA goals.

Reach out to us to discuss how to get into your dream school, framing your career goals and personal background in the most compelling way possible.