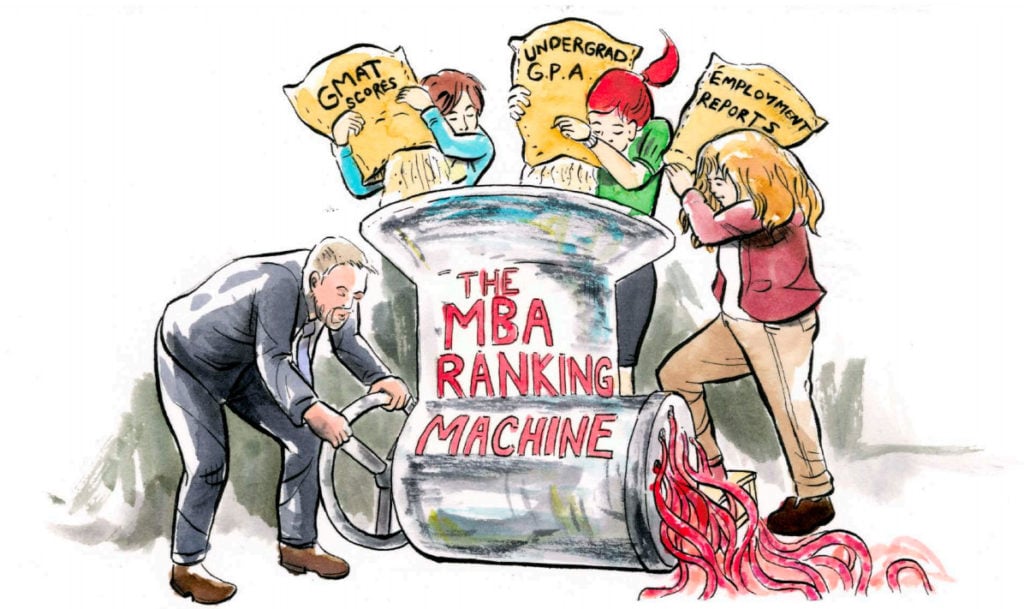

Choosing the right MBA program could be the most important decision in your professional career. Before you start using rankings to make this decision, shouldn’t you learn a little bit about how they work?

Rankings are ultimately designed by publications to create controversy and therefore increase readership. If they admitted that the quality of schools doesn’t often change radically from year to year, no one would need to read the article.

These are key points to consider when consulting the 2025–2026 edition of the U.S. News “Best Business Schools” ranking. This ranking is often seen as the most accurate and prestigious one available, and yet it fails, like other MBA rankings, to grade business schools fairly and consider them in their proper context.

If you want a stable list of the leaders in MBA education that is not designed to artificially change the rankings each year to draw readers, see our directory of top MBA programs, which doesn’t focus on a ranking formula, but on the curriculum, class profile, employment report, and culture of each MBA program.

| 1. | UPenn Wharton |

| 2. | Northwestern Kellogg |

| 2. | Stanford GSB |

| 4. | Chicago Booth |

| 5. | MIT Sloan |

| 6. | Dartmouth Tuck |

| 6. | Harvard Business School |

| 6. | NYU Stern |

| 9. | Columbia Business School |

| 10. | Yale SOM |

| 11. | Berkeley Haas |

| 11. | UVA Darden |

| 13. | Duke Fuqua |

| 13. | Michigan Ross |

| 15. | Cornell Johnson |

| 16. | UT Austin McCombs |

| 17. | Emory Goizueta |

| 18. | Carnegie Mellon Tepper |

| 18. | UCLA Anderson |

| 18. | Vanderbilt Owen |

| 21. | Georgia Tech Scheller |

| 22. | Indiana Kelley |

| 22. | UW Foster |

| 24. | Georgetown McDonough |

| 24. | Ohio State Fisher |

| 24. | USC Marshall |

| 24. | Washington Olin |

For the U.S. News ranking, US business schools are evaluated using several different metrics, divided into three categories, each consisting of several individual measures:

These categories and individual measures are all the same as last year, except that “Placement Success” has been renamed to “Attainment Success” (while still including all the same measures).

No new measures have been introduced this time around, and the relative weight of all the different measures has stayed the same. Let’s break down the three categories in turn.

Attainment Success includes four measures that are focused on the short-term career outcomes of graduates from the program:

The “salary by profession” measure was introduced last year and remains in place this year. It aims to evaluate where the mean starting salary of a school’s graduating class sits within a given employment bucket (e.g., Consulting, Finance) in relation to the other schools in the ranking.

The Quality Assessment category contains two measures focused on how the schools are rated by those presumed to know best:

These are the only qualitative measures in the U.S. News MBA ranking. Below, we’ll dig into why they’re not very reliable measures.

Student Selectivity covers, essentially, how difficult it is to get into each program, looking at three measures:

In 2023–2024, U.S. News adopted the measure of median GMAT and GRE scores, as opposed to the traditional mean score. In 2024–2025, this change spread further, and the median undergraduate GPA (again instead of the mean) was taken into account. Both changes have remained in place this year.

We cover why this is important, particularly in relation to the GMAT and GRE, below.

A new change for 2025 is a different way of treating scores from the new (Focus) and old versions of the GMAT.

U.S. News states that “collected data on both the old GMAT test and the new GMAT test” were used. “If an MBA program’s school reported both tests for fall 2024 entrants, then both tests were used in the rankings after being converted to the percentile distribution weighted by the proportion of test-takers for each GMAT test.”

This is a sensible change that avoids any potential bias to the stats that could result from schools reporting scores from only one version of the test.

| Categories | 2022–2023 | 2023–2024 | 2024–2025 / 2025–2026* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attainment Success (Total) | 35% | 50% | 50% |

| Employment Rate | At Graduation: 7% | At Graduation: 10% | At Graduation: 7% |

| +3 Months: 14% | +3 Months: 20% | +3 Months: 13% | |

| Total: 21% | Total: 30% | Total: 20% | |

| Mean Starting Salary & Bonus | 14% | 20% | 20% |

| Salary by Profession | N/A | N/A | 10% |

| Quality Assessment (Total) | 40% | 25% | 25% |

| Peer Assessment | 25% | 12.5% | 12.5% |

| Recruiter Assessment | 15% | 12.5% | 12.5% |

| Student Selectivity (Total) | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| GMAT & GRE Scores | 16.25% (mean) | 13% (median) | 13% (median) |

| Undergraduate GPA | 7.5% (mean) | 10% (mean) | 10% (median) |

| Acceptance Rate | 1.25% | 2% | 2% |

In the 2023–2024 ranking, median GMAT/GRE scores replaced mean GMAT/GRE for the first time. U.S. News wrote that this change was intended to “limit the rankings impact of outlier scores, including low scores from otherwise promising applicants.”

Though any external commentary on how MBA programs are reacting to this change is necessarily speculative—schools don’t release the kinds of data that would be required to analyze the full impact—the use of median test scores is likely affecting admissions decisions in subtle ways.

Namely, extremely high scores may become less valuable, and extremely low scores may represent less of a handicap.

Imagine two artificially simplified classes an MBA program could recruit:

The median for both groups is 730, but the means would be 710 and 722 respectively. Under the old ranking system, Group B’s higher scores would be more likely to sway the admissions committee, as the 750 and 780 would bring up the school’s rating in the test score section. But under the new system, there is no inherent reason to choose Group B over Group A.

Of course, there are other reasons that AdComs might still prefer high GMAT scores:

This same logic applies to undergraduate GPAs going forward. While an extremely high or low GPA might not have the same impact it used to, your GPA will still be a crucial factor in the strength of your profile.

In the past, we’ve been vocal in our criticism of the weight U.S. News places on the less objective metrics in their ranking methodology—namely the “peer assessment” and “recruiter assessment” portions of their ranking methodology.

It might seem like a fair approach: allow all 131 schools under consideration to grade each other, giving every program equal input for the ranking.

But do you really think that, for example, Clemson University—ranked #95—has any knowledge or interest in the #1-ranked Wharton’s activity? The same is true in reverse: Wharton has no real insight into Clemson. The fact is, the two schools have a completely different target group of applicants, and asking the two schools to grade one another makes no sense.

U.S. News does provide a “don’t know” option allowing respondents to opt out of rating any particular school. It’s safe to assume that this option is not used consistently or conscientiously in practice; if it were, there would be a whole lot of “don’t knows” and very little data to go on.

And think about the schools that are competing, especially for the top positions. Schools like Stanford and Wharton have a vested interest in downgrading Harvard: They won’t give Harvard an implausibly terrible score, but they will go as low as they think they can get away with. And why wouldn’t they? These schools are ranked against each other; to climb the rankings, you have to push someone else down.

In the 2023–2024 rankings, U.S. News halved the influence of peer assessment over a school’s final ranking (from 25% to 12.5%). This was a welcome change, as reducing the weight of the peer assessment allows schools to be evaluated based on less subjective—and less easily manipulated—criteria.

While the change shows some recognition of the problems with this measure, it does not, of course, fully remove its influence.

As always, we advise that MBA applicants consider the broader context surrounding MBA rankings and take a balanced approach to the emphasis they place on them. Selecting the right MBA program is a very personal decision, and working with an MBA admissions counselor can help you make an informed, strategic decision.

The recruiter assessment has also been, historically, problematic, especially as some recruiters will know a lot about a school they’ve drawn from in the past, but not about schools they’ve never worked with. Indeed, no one could possibly know enough about every school to give each a proper, informed ranking.

It’s also worth pointing out that because the names of the recruiters surveyed by U.S. News were supplied by the schools, the objectivity of the review is compromised. An MBA program could supply the name of an employer where they have placed a smaller number of people very successfully and leave out a company where they have placed many people with mixed results. This way, the schools can skew the results in their favor.

Questions of objectivity or manipulation aside, we also must consider that, for some schools, a very strong, meaningful reputation with regional recruiters might be overshadowed by a weaker national reputation.

For instance, take a school with excellent graduate employment rates, close to 100%, beating even the top programs (see below). Such schools can still score poorly with recruiters, hurting their overall ranking, simply because they place most of their graduates in the local area and are relatively unknown nationally.

This reveals a very real shortcoming of the U.S. News ranking: Someone interested in, say, a tech job in the Pacific Northwest could miss out on the programs best positioned to get them one, simply because the U.S. News methodology privileges high peer assessment, and more specifically, high national peer assessment.

A school that places many graduates regionally will receive poor ratings from recruiters elsewhere—even though those in the know will realize that it’s an excellent choice for students targeting jobs in that region.

In 2023, U.S. News reduced the weight of the recruiter assessment (from 15% to 12.5%), mitigating the influence that this flawed metric has on a school’s overall ranking. Although this change is encouraging, the reduction in weight merely reduces the harm this measure can do, rather than addressing the fundamental flaws in its design.

“Gauging a school’s reputation with employers accurately would require more data, such as which companies chose to hire a given MBA program’s graduates. Programs that place into the most desirable employers—such as Google, Goldman Sachs, or McKinsey—prove that they have a great reputation with employers.

“At Menlo Coaching, we advise our clients based on a proprietary data set showing which companies hired each MBA program’s graduates.”

By feeding employment rates directly into their ranking, U.S. News fails again to consider the broader context of certain data points. In 2023–2024, U.S. News unfortunately increased the value of employment rates at graduation (from 7% to 10%) and after graduation (from 14% to 20%).

It is a welcome change that the publication decided to reverse course and reduce the weight of these factors in the 2024–2025 ranking to 7% and 13% respectively.

Consider the case of Harvard and Stanford. Stanford, famously one of the most prestigious universities and business schools in the world, has a particularly low employment rate at graduation (often hovering around 60% at graduation, 80% three months after). Harvard has similarly dismal employment rates relative to its stature.

This doesn’t make sense at first glance: How can two of the most renowned business schools in the world have worse employment rates than less prestigious schools?

It’s because graduates from Harvard and Stanford, unlike those from other schools, are unemployed out of choice, not because they can’t find a job. Most Harvard and Stanford alumni could, of course, get a job. But they wait for the perfect offer.

Therefore, the low employment rates do not reflect weakness, but come instead from a point of strength. Harvard and Stanford students have so many opportunities that they can afford to wait for the perfect opportunity for them.

This is not reflected in the U.S. News ranking, and it is only because these programs do so well in the other categories that they are able to maintain their high positions.

Reading through other current rankings of MBA programs, such as those of Businessweek and the Financial Times, another question arises: How can they vary so widely?

In other articles, you can find full breakdowns of Businessweek’s and FT’s rankings. The following table compares the results of the three rankings at a glance:

| Business School | U.S. News | Businessweek | Financial Times* |

| UPenn Wharton | 1st | 2nd | 1st |

| Northwestern Kellogg | 2nd | 5th | 4th |

| Stanford GSB | 2nd | 1st | —** |

| Chicago Booth | 4th | 7th | 9th |

| MIT Sloan | 5th | 11th | 3rd |

| Dartmouth Tuck | 6th | 6th | 11th |

| Harvard | 6th | 4th | 6th |

| NYU Stern | 6th | 12th | 15th |

| Columbia | 9th | 9th | 2nd |

| Yale SOM | 10th | 17th | 13th |

| Berkeley Haas | 11th | 3rd | 8th |

| UVA Darden | 11th | 10th | 11th |

| Duke Fuqua | 13th | 13th | 5th |

| Michigan Ross | 13th | 14th | 14th |

| Cornell Johnson | 15th | 8th | 6th |

| UT Austin McCombs | 16th | 21st | 17th |

| Emory Goizueta | 17th | 16th | 20th |

| Carnegie Mellon Tepper | 18th | 15th | 22nd |

| UCLA Anderson | 18th | 19th | 10th |

| Vanderbilt Owen | 18th | 27th | 25th |

| Georgia Tech Scheller | 21st | 23rd | 29th |

| Indiana Kelley | 22nd | 30th | —** |

| UW Foster | 22nd | 18th | 16th |

| Georgetown McDonough | 24th | 22nd | 19th |

| Ohio State Fisher | 24th | 37th | —** |

| USC Marshall | 24th | 20th | 23rd |

| Washington Olin | 24th | 30th | 18th |

| UNC Kenan–Flagler | 28th | 28th | 24th |

| Rice Jones | 29th | 25th | 17th |

| Georgia Terry | 29th | 23rd | 28th |

| UF Warrington | 38th | — | 21st |

These differences can largely be explained by looking at the methodologies used by the different publications, the specific measures they’re taking into account.

Businessweek’s “Compensation” ranking, for example, matches the U.S. News ranking quite well. But as the other subrankings begin to diverge, the overall ranking from Businessweek becomes less and less aligned with that of U.S. News. Other subrankings such as “Learning” and “Networking” are based on student surveys, which U.S. News doesn’t use.

Similarly, FT looks at various diversity measures and a “Carbon Footprint Rank” that are not included in the other rankings.

There are also anomalies such as the exclusion of Stanford from the current FT list, apparently because the publication didn’t receive enough survey responses from its alumni. It’s safe to say FT does not actually think Stanford falls outside the top 100; rather, the omission indicates Stanford doesn’t have sufficient interest in the FT list to put in the effort to compete.

We’re not trying to make any claim about which publication’s methodology is best here. Rather, the variety of approaches taken to creating these kinds of rankings, and the stark differences in their results, should make you think twice about taking any ranking as gospel.

Like it or not, the U.S. News ranking is the most prestigious and relied-upon list of “top” US business schools. This fact, combined with the flawed methodology described in great detail above, makes it a particularly troublesome list.

The ranking will continue to generate new headlines every year, and many judgments about the quality of MBA programs—whether deserved or not—will be formed as a result. But at least you, the informed reader, now understand how U.S. News mischaracterizes key data points and fails to live up to standards of objectivity.

So approach the list with caution, and take the U.S. News ranking with a grain of salt.

Once you determine roughly which schools you are qualified to attend—and rankings can definitely factor into this initial list—we encourage you to leave the rankings behind and instead focus on the practical questions that will help you figure out which MBA program will provide value to your career. These are simple, practical questions:

Answering these questions will help you find an MBA program that can enhance your career. From there, we recommend you look into MBA admissions consulting services to assess whether your target programs are realistic and maximize your chances of getting in.