The Financial Times global MBA rankings for 2025 go beyond US business schools to compare 100 MBA programs from all over the world. This broad perspective is welcome, especially for international applicants.

Unfortunately, it is this same global focus that poses problems for the objectivity of the ranking, and any applicant looking to the Financial Times (FT) for guidance should keep the following observations in mind when consulting the list.

And meanwhile, if you want a stable list of the long-term leaders in MBA education, see our directory of top MBA programs, which focuses not on a ranking formula but on the factors that make each program valuable to students.

| 1. | UPenn Wharton | US |

| 2. | Columbia Business School | US |

| 3. | IESE | Spain |

| 4. | INSEAD | France |

| 4. | SDA Bocconi | Italy |

| 6. | MIT Sloan | US |

| 7. | London Business School | UK |

| 8. | ESADE | Spain |

| 9. | HEC Paris | France |

| 10. | Northwestern Kellogg | US |

| 11. | Duke Fuqua | US |

| 12. | CEIBS | China |

| 13. | Harvard Business School | US |

| 13. | Cornell Johnson | US |

| 15. | Berkeley Haas | US |

| 15. | SUFE College of Business | China |

| 17. | Chicago Booth | US |

| 18. | IE Business School | Spain |

| 19. | UCLA Anderson | US |

| 20. | Dartmouth Tuck | US |

| 20. | UVA Darden | US |

| 22. | IMD | Switzerland |

| 22. | Nanyang Business School | Singapore |

| 24. | Yale SOM | US |

| 25. | Peking Guanghua | China |

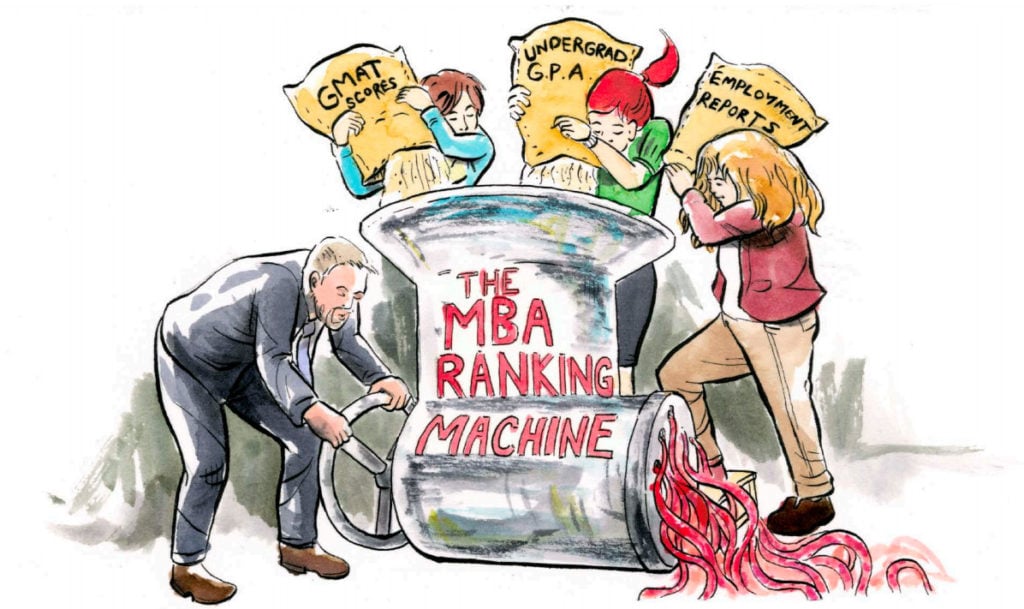

The Financial Times includes the following data in its ranking, with the weighting given in parentheses:

The survey is filled out by alumni three years after they obtained their MBA; the responses from 2025, 2024, and 2023 were used in the most recent ranking.

A large part of the survey consists of questions about pre- and post-MBA salaries and positions, with only a small proportion comprising qualitative questions—the “aims achieved” and “careers service” ranks, based on respondents’ personal ratings of these factors.

The “school data” portion of the ranking includes a variety of diversity measures concerning both students and faculty, as well as employment rates and sustainability measures, and the proportion of faculty holding doctorates.

The research category is unique to the FT ranking, measuring the number of articles published by faculty in 50 selected academic and practitioner journals, weighted relative to the faculty’s size. The quality or importance of these publications is not taken into account.

FT also states that a minimum of 20 percent of alumni must respond to the survey for that school to be included. That’s how it came to pass that important schools like Stanford and Kelley were omitted entirely from this year’s list.

Although the qualitative component of the Financial Times ranking makes up only a small portion of the overall score and does not exert too strong an influence on the final result, it is still worth noting that the results of any student survey will always be arbitrary.

When students are asked to rank their school, they have nothing to compare it against. After all, they are not attending multiple programs at once! And not only are they unable to grade their program relative to another, but their feedback is also relative to their expectations.

A student at an M7 program, for example, expects an amazing experience based on the prestige of the program. If their experience turns out to be “great” instead of amazing, the student might give their school a lower score than someone who expects a “good” experience but receives a great one.

In terms of quantitative data, the Financial Times treats various metrics differently than other ranking bodies. Instead of focusing on GMAT scores and GPAs, FT looks at diversity, both in gender and in nationality. It’s a fresh approach, and rewarding the international character of a school might make this ranking interesting for some.

But in general, it creates a bias toward non-US schools, as they tend to have a more diverse student and faculty set—especially the European schools.

Non-US schools are also favored in a more significant way by how the FT factors compensation into the ranking. It corrects the average salary of the alumni using the USD purchasing power parity (PPP) equivalent. Schools with a high number of alumni working in lower-income countries (typically non-US schools) are therefore disproportionately favored.

Reading through other current rankings of MBA programs, such as those of U.S. News and Businessweek, another question arises: How can they vary so widely?

In other articles, you can find full breakdowns of the U.S. News and Businessweek rankings. The following table compares the results of the three rankings at a glance:

| Business School | U.S. News | Businessweek | Financial Times* |

| UPenn Wharton | 1st | 2nd | 1st |

| Northwestern Kellogg | 2nd | 5th | 4th |

| Stanford GSB | 2nd | 1st | —** |

| Chicago Booth | 4th | 7th | 9th |

| MIT Sloan | 5th | 11th | 3rd |

| Dartmouth Tuck | 6th | 6th | 11th |

| Harvard | 6th | 4th | 6th |

| NYU Stern | 6th | 12th | 15th |

| Columbia | 9th | 9th | 2nd |

| Yale SOM | 10th | 17th | 13th |

| Berkeley Haas | 11th | 3rd | 8th |

| UVA Darden | 11th | 10th | 11th |

| Duke Fuqua | 13th | 13th | 5th |

| Michigan Ross | 13th | 14th | 14th |

| Cornell Johnson | 15th | 8th | 6th |

| UT Austin McCombs | 16th | 21st | 17th |

| Emory Goizueta | 17th | 16th | 20th |

| Carnegie Mellon Tepper | 18th | 15th | 22nd |

| UCLA Anderson | 18th | 19th | 10th |

| Vanderbilt Owen | 18th | 27th | 25th |

| Georgia Tech Scheller | 21st | 23rd | 29th |

| Indiana Kelley | 22nd | 30th | —** |

| UW Foster | 22nd | 18th | 16th |

| Georgetown McDonough | 24th | 22nd | 19th |

| Ohio State Fisher | 24th | 37th | —** |

| USC Marshall | 24th | 20th | 23rd |

| Washington Olin | 24th | 30th | 18th |

| UNC Kenan–Flagler | 28th | 28th | 24th |

| Rice Jones | 29th | 25th | 17th |

| Georgia Terry | 29th | 23rd | 28th |

| UF Warrington | 38th | — | 21st |

Differences can largely be explained by looking at the methodologies used by the different publications, the specific measures they’re taking into account.

FT’s “carbon footprint,” “ESG and net zero teaching,” and “research” ranks are all unique to this ranking, attempting to capture factors not considered in the other rankings, which naturally affects the results.

Compared to FT, the Businessweek ranking is substantially more qualitative, with a much bigger focus on asking survey respondents for their personal ratings of different elements of the school. It also includes a section on inclusion, but it has less weight in the ranking than with FT.

U.S. News, meanwhile, has a more statistical focus and does not use student surveys. It looks at factors like median GMAT scores and mean starting salaries rather than asking about students’ personal assessment of the program. This again naturally leads to quite different results.

There are also anomalies such as the exclusion of Stanford from the current FT list, apparently because the publication didn’t receive enough survey responses from its alumni. It’s safe to say FT does not actually think Stanford falls outside the top 100; rather, the omission indicates Stanford doesn’t have sufficient interest in the FT list to put in the effort to compete.

We’re not trying to make any claim about which publication’s methodology is best here. Rather, the variety of approaches taken to creating these kinds of rankings, and the stark differences in their results, should make you think twice about taking any ranking as gospel.

While it is a laudable goal to publish a list of international business schools, giving all programs an equal opportunity to compete for top positions, the reality is that FT favors non-US programs through an unfair and out-of-context salary metric. For this reason, we do not feel that all entries in the “top 25” have truly earned their position.

However, when it comes to international MBA rankings, the Financial Times is something of a “gold standard” and is more trustworthy than any other international ranking currently in publication, particularly for candidates solely interested in diversity or the international quality of a business school.

(For further discussion on the criteria that influence international MBA rankings, we recommend reading our analysis of The Economist’s MBA rankings, despite the ranking’s 2022 discontinuation.)

Once you determine roughly which schools you are qualified to attend—and the rankings can definitely factor into this initial list—we encourage you to leave the rankings behind and instead focus on the practical questions that will help you figure out which MBA program will provide value to your career. These are simple, practical questions:

Answering these questions will help you find the right MBA program to enhance your career.

Navigate through the intricacies of MBA rankings with our expert MBA consultants and gain clarity on your journey toward your dream school.