LinkedIn came out with the 2025 version of its global “Best MBA Programs for Career Growth” ranking in September. With its huge user base providing extensive data to work with, LinkedIn seems uniquely well placed to construct this kind of ranking.

Yet the results are nothing if not controversial. Unusually high rankings for the Indian School of Business (ISB) and Oxford Saïd, and spots outside the top 25 for such mainstays as Michigan Ross and UCLA Anderson, have been particular points of contention.

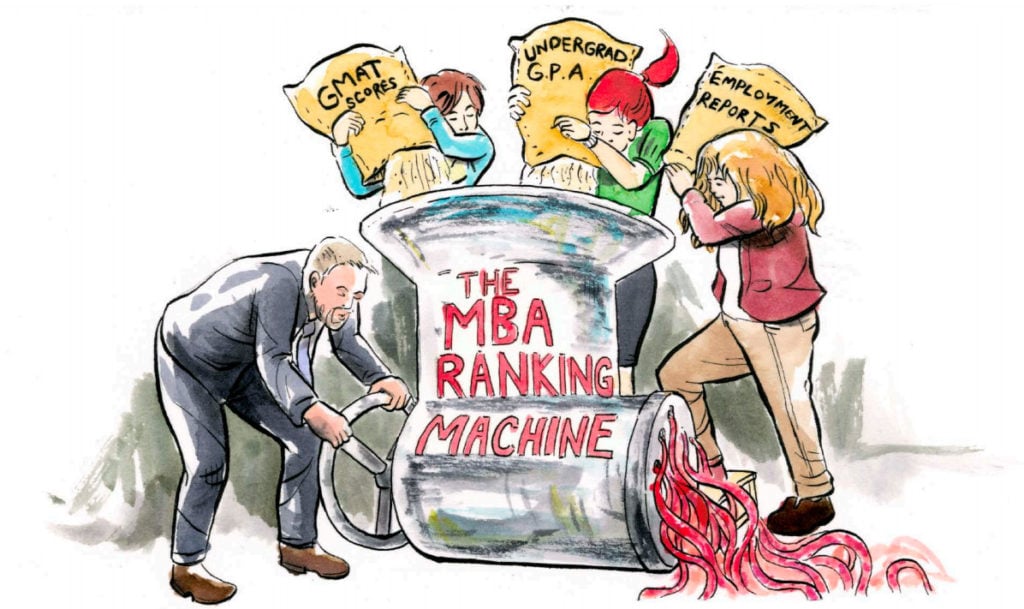

This ranking and others are of course constructed precisely to stir up drama, getting readers’ attention with unlikely claims and artificially shuffling schools up and down the ranking from year to year. Let’s look at how LinkedIn’s ranking was constructed.

| Ranking | Program | Country |

| 1. | Stanford GSB | US |

| 2. | Harvard | US |

| 3. | INSEAD | France |

| 4. | UPenn Wharton | US |

| 5. | ISB | India |

| 6. | Northwestern Kellogg | US |

| 7. | MIT Sloan | US |

| 8. | Dartmouth Tuck | US |

| 9. | Columbia | US |

| 10. | LBS | UK |

| 11. | Chicago Booth | US |

| 12. | Oxford Saïd | UK |

| 13. | Duke Fuqua | US |

| 14. | Yale SOM | US |

| 15. | Berkeley Haas | US |

| 16. | IIM Calcutta | India |

| 17. | IIM Ahmedabad | India |

| 18. | UVA Darden | US |

| 19. | Cornell Johnson | US |

| 20. | IIM Bangalore | India |

| 21. | NYU Stern | US |

| 22. | IESE | Spain |

| 23. | IMD | Switzerland |

| 24. | HEC Paris | France |

| 25. | Emory Goizueta | US |

LinkedIn’s MBA ranking, while it attempts to measure some of the same factors as other rankings, is unique in attempting to do so using only the site’s own user data. No surveys or external stats went into the ranking—only existing LinkedIn data.

The methodology of the LinkedIn ranking is based on five “pillars,” each made up of one to three metrics:

The first four pillars are all weighted equally, while gender diversity is given half the weight of the others. This means that each pillar counts for two-ninths of the total ranking, except gender diversity, which is one-ninth.

A “where they stand out” feature in some of the schools’ rankings highlights if that school was in the top 5 for a particular pillar, but does not give its exact ranking for that pillar. If a school wasn’t in the top 5, the ranking gives no information at all about how it did for that pillar, making the strengths and weaknesses of most schools unclear.

“Recent cohorts” are defined as those graduating from 2019 to 2024. The methodology doesn’t specify whether all metrics are equally weighted within each pillar, nor how exactly each metric is calculated. It’s therefore difficult to assess the reliability of the analysis.

The scope of the ranking is ostensibly global, but it excludes mainland China, because LinkedIn no longer operates there. Therefore, no Chinese B-schools appear in the list. The list also only considers full-time MBA programs; executive and part-time MBAs are not included.

There are a few major flaws in the methodology of the LinkedIn ranking that make its results unreliable.

First, the “network strength” pillar, focused on the size and “quality” of alumni’s LinkedIn networks, is highly gameable and virtually meaningless. Many people accept LinkedIn connections indiscriminately even if they don’t know the person inviting them and have no intention of speaking to them—let alone meaningfully advancing their career.

Fundamentally, no one would seriously argue that the person with the highest number of LinkedIn connections is the most successful. It would be just as reasonable to interpret the number as an indication that they’ve spent a lot of time on the site, looking for work.

Speculatively, this could even bias the results toward schools in countries where the work culture places a strong emphasis on this kind of scattershot networking—and, of course, those where LinkedIn is particularly ubiquitous.

A similar issue arises with the “hiring and demand” pillar: The complete reliance on LinkedIn hiring and messaging data means that the ranking completely ignores all hiring that didn’t take place through LinkedIn. Given the importance of on-campus recruiting for desirable post-MBA industries like consulting and finance, this is a major blind spot.

A secondary issue with this pillar is that no attempt is made to distinguish between different types of companies or even different industries.

One could imagine a LinkedIn ranking that looked at how successfully different programs placed candidates into MBB consulting firms or PE megafunds; this ranking instead looks at whether graduates were able to get … a job.

The unreliability of LinkedIn data is also a concern. For example, it’s not uncommon for students of one program who did a study-abroad semester at another school to list both schools on their profiles.

We have no indication of how the ranking team would deal with such ambiguity, but it’s hard to imagine they’d have the capacity to check each individual really got their degree at the school they list.

It’s also a simple fact that not everyone keeps their LinkedIn profile up to date with every detail of their education and professional activities. A user who didn’t list their MBA program on their profile would necessarily be left out of this analysis; one who listed their job title inaccurately, or didn’t list it at all, would skew the results in a different way.

There’s also the fact that LinkedIn does not have data about its users’ salaries—a crucial data point in most other MBA rankings. In this case, the data is not unreliable but simply missing, meaning that the ranking fails to capture what is arguably the single most important factor for most MBA applicants.

Finally, as mentioned above, an overarching issue is that the way LinkedIn describes its methodology is vague and incomplete. Without more specificity, one could imagine a variety of plausible ways to calculate such metrics as “labor market demand” or “how connected alumni of the same program are to each other”—but we don’t know which ones the LinkedIn team chose.

Nor do we have any indication of the specific scores each school received on each pillar; or the relative importance of the different measures within each pillar; or how ambiguous job titles or alma maters were disambiguated.

A lack of clarity on such important details raises questions about how much care went into the ranking process itself.

To get some perspective on the LinkedIn rankings, it’s useful to compare them to another prominent global MBA ranking, that of the Financial Times.

The following table compares the two rankings at a glance:

| Program | Country | Financial Times | |

| Stanford GSB | US | 1st | —* |

| Harvard | US | 2nd | 13th |

| INSEAD | France | 3rd | 4th |

| UPenn Wharton | US | 4th | 1st |

| ISB | India | 5th | 27th |

| Northwestern Kellogg | US | 6th | 10th |

| MIT Sloan | US | 7th | 6th |

| Dartmouth Tuck | US | 8th | 20th |

| Columbia | US | 9th | 2nd |

| LBS | UK | 10th | 7th |

| Chicago Booth | US | 11th | 17th |

| Oxford Saïd | UK | 12th | 26th |

| Duke Fuqua | US | 13th | 11th |

| Yale SOM | US | 14th | 24th |

| Berkeley Haas | US | 15th | 15th |

| IIM Calcutta | India | 16th | 61st |

| IIM Ahmedabad | India | 17th | 31st |

| UVA Darden | US | 18th | 20th |

| Cornell Johnson | US | 19th | 13th |

| IIM Bangalore | India | 20th | 57th |

| NYU Stern | US | 21st | 31st |

| IESE | Spain | 22nd | 3rd |

| IMD | Switzerland | 23rd | 22nd |

| HEC Paris | France | 24th | 9th |

| Emory Goizueta | US | 25th | 45th |

| UCLA Anderson | US | 27th | 19th |

| IE | Spain | 35th | 18th |

| ESADE | Spain | 46th | 8th |

| SDA Bocconi | Italy | 47th | 4th |

| CEIBS | China | —** | 12th |

| SUFE College of Business | China | —** | 15th |

| Nanyang | Singapore | — | 22nd |

| Peking Guanghua | China | —** | 25th |

Now, the FT ranking has its own quirks; we’re not trying to set it up as a perfect list to contrast with LinkedIn’s kooky one. But the big differences are revealing of potential biases in LinkedIn’s methodology:

Apart from the last point, any explanations of these differences are necessarily speculative—especially given the previously mentioned ambiguity surrounding LinkedIn’s methodology.

But we do see that most of the Indian schools included are described as “top 5 for networking.” In fact, every school in the list that has this designation is an Indian school. In other words, the shoddy networking metrics in the methodology seem to have created a bias toward these schools that boosted their rankings significantly.

In any case, this and other disparities are striking enough that they should give you pause and make you take both rankings with a grain of salt.

Once you determine roughly which schools you are qualified to attend—and MBA program rankings can be useful tools for building this initial list—we encourage you to leave the rankings behind and instead focus on the questions that will help you figure out which MBA program will provide value to your career. These are simple, practical questions:

Answering these questions will help you find the right MBA program to enhance your career.

Navigate through the intricacies of MBA rankings with our expert MBA consultants and gain clarity on your journey toward your dream school.